Australia already has a staggering 2,312 children aged 0-4 years old on a potentially dangerous psychiatric drug. Now there is a recommendation to screen 1.25 million 0-3-year-olds for “mental illness” and “emerging mental illness”. The numbers of infants and toddlers on potentially dangerous mind-altering psychiatric drugs is set to greatly increase.

This recommendation is a result of Australia’s Productivity Commission’s Inquiry into Mental Health. The Productivity Commission is the Australian Government’s main review and advisory body on economic policy. Specifically, this inquiry was called to determine whether the current mental health programs are effective and if they deliver the best outcomes for children, families and the economy. Their Final Report contains some alarming proposals which will adversely affect our children.

Submissions are now being called for by a Federal Parliament Committee who are investigating the findings in the Final Report. Submissions close 1 November 2021.

Prof. Harvey Whiteford was appointed an Associate Commissioner for this inquiry. He is the psychiatrist who designed and oversaw the implementation of Australia’s National Mental Health Strategy (which commenced in 1992). Between 2008 and 2012 alone, his company, Harvey Whiteford Medical PTY LTD, received more than $1.1 million from the Department of Health for providing planning and services for national mental health reform, etc.1

The final report of the Inquiry states, “Costs have been rising over time with no clear indication that the mental health of the population has improved.”

The final report of the Inquiry states, “Costs have been rising over time with no clear indication that the mental health of the population has improved.”

Despite this statement, the Final Report reveals that the real reasons behind the failure of Australia’s mental health system were not adequately investigated as part of the inquiry. Instead of addressing the complete lack of efficacy of psychiatric “treatment” and the clear evidence of the potential harm that these “treatments” can potentially cause, the inquiry seems to have been side-lined into the proposition that the failure of the current system is to do with lack of funding.

If psychiatric “treatments” were working. there would be a reduction in children and adults requiring assistance.

Instead of the Inquiry tackling relevant issues such as the complete lack of scientific testing behind psychiatric disorders, we are told more funding and more subjective mental health screening will fix what is broken.

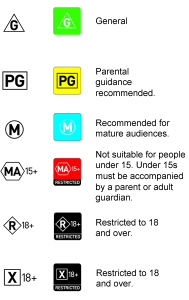

Psychiatric Screening is the use of a highly subjective checklist usually based on the DSM or DC:0-5 (for children aged 0-5 years) in order to diagnose a child or adult with a “mental illness.” From these screenings and subsequent referrals of identified children, infants, children and toddlers can be “diagnosed” and prescribed stimulants, antidepressants and or antipsychotic drugs, placing them at risk of ill-health and potentially dangerous side effects─some even deadly.

What are the Recommendations & Screening Based on?: The Final Report and Australia’s failing National Mental Health Strategy are predominantly based on psychiatry’s main manual used in Australia to diagnose “mental disorders,” the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM).2

What are the Recommendations & Screening Based on?: The Final Report and Australia’s failing National Mental Health Strategy are predominantly based on psychiatry’s main manual used in Australia to diagnose “mental disorders,” the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM).2

With regards to zero to three-year-olds, “diagnosis” is often made using DC:0-5, the Diagnostic Classification of Mental Health and Developmental Disorders of Infancy and Early Childhood.

This manual references the DSM. The Australian Association for Infant Mental Health now promotes where training on how to use DC:0-5 can be done.3

Symptoms of so-called psychiatric disorders in 0-3-year-olds per this diagnosing manual include difficulty sleeping, tantrums, losing track of a favourite stuffed animal and hyperactivity.

Psychiatrists themselves state there are no tests for psychiatric diagnosis (no x-ray, scan, blood or urine test) to determine any infant, child or adult has any psychiatric diagnosis.4 As of January 2021, Medicare uses DSM IV and the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme which funds psychiatric drugs is using DSM 5.5

PROPOSALS OF GRAVE CONCERN INCLUDE:

1.25 Million Zero to Three-Year-Old Children to be Screened for “Mental Illness”: The recommendation is that these children will be screened for “mental illness” or “emerging mental illness.” The recommendation as written seems innocuous – checking emotional development, and of course, we all want to see our children healthy. However as one expert stressed when advising Australia’s federal government, another language for “emotional and social well-being” should be found rather than using mental illness and mental health terminology, this is a whole different ball game. [Productivity Commission Final Report Overview, Vol. 1, p. 20.]

This same expert also said that despite the different language used, the educational system (“who use well-being”) and the health services system (who use disorder & DSM-type diagnoses), a diagnosis is often required for the child to receive additional services.6 Terminology is being changed in an attempt to hide what is really proposed for our infants.

The Productivity Commission Reports are clear about screening and diagnosis:

- The Final Report on page 204, covers how early childhood screening could lead to psychiatric drugs. The same page also covers that for children “at-risk” or diagnosed with “mental illness”, medication is an option.

- “The definition of infant mental health is still a matter of debate among experts, although more formalised approaches to diagnosis and treatment are being developed and implemented.”

- “But additional screening and support tools can be valuable in the prevention of mental illness or early intervention where it is required.”

- “Consistent screening of social and emotional development should be included in existing early childhood physical development checks to enable early intervention.” One of the Reports defines what early intervention programs are: They “assist a child, young person or adult through the early identification of risk factors and/or the provision of timely treatment for problems that can alleviate potential harms caused by mental illness.” Treatment for “mental illness” can include psychiatric drugs.

- One of the Commission’s points of reference is, “Zero to Three,” an organisation that published and relies upon DC:0-5, the Diagnostic Classification of Mental Health and Developmental Disorders of Infancy and Early Childhood.7

A Freedom of Information Request to the Productivity Commission requesting documents used for this recommendation revealed a table titled, “Infants – are maternal child health services equipped to handle mental health? Do they have people to refer to?” This same Freedom of Information request also asked for copies of the minutes of any meetings held covering this recommendation for 0-3 year-olds, but no such minutes exist.

The result of such a plan? The number of infants and toddlers already prescribed potentially dangerous mind-altering drugs is set to greatly increase. Screening questions on checklists used to screen are so subjective that any child could be at risk of being labelled mentally ill and potentially recommended for a prescription of psychiatric drugs.

Symptoms for So-Called Psychiatric Disorders for 0 to 3-Year-Olds Include:

Irregular feeding patterns, difficulty sleeping, crying, calling for absent parent, separation or stranger anxiety, tantrums, shyness, losing track of a favourite stuffed animal and hyperactivity.

All of the above could be normal childhood behaviour and if there really is a problem it will not be found and rectified with such screening. Instead, the infant or child could receive a psychiatric diagnosis and psychiatric drugs.8

When New Zealand introduced the 4-year-old screening, within 4 years prescriptions of antidepressants to 0-4-year-olds increased by 140%.9

In 2007/08 Australia had Babies Under One Year Old on Psychiatric Drugs. At that time there were:

- 201 children aged under 3 on antidepressants (48 aged under 1 year old)

- 59 children aged under 3 on antipsychotics ( 5 aged under 1 year old) and

- 46 children aged under 3 on ADHD drugs in 2007.10

Since that time the Department of Health and Services Australia will no longer provide the numbers of children on psychiatric drugs by age, under 6.

In 2015 there were:

- 4,974 children aged 2-6 years on ADHD drugs,

- 1,459 children aged 2-6 years on antidepressants

- 1,384 aged 2-6 on antipsychotics (total of 7,817 children aged 2-6 years).11

And we do know that in 2018/19 there were a staggering 2,312 children aged under five on a psychiatric drug.12

The solution can’t be more screening or more of the same failing “treatments” and programs.

Early Intervention for “Emerging Mental Illness” Means the infant or child doesn’t have it but they ‘could’ get it in the future. How non-scientific is this? Essentially it is an arbitrary list of behavioural symptoms, which psychiatrists claim can predict the onset of “mental illness.” The psychiatrists can then treat the child to “prevent” the “disorder.” One example of this is “emerging psychosis.” Evidence shows, 82% to 90% will not go on to develop psychosis within a year of diagnosis. Despite this the premise is that they should be treated now. These screenings are a disaster for infants, toddlers, children and youth.13

The Australian Government has issued 67 psychiatric drug warnings to warn of the risk of agitation, aggression, increased blood pressure, hallucinations, life-threatening heart problems, suicidal behaviour and possible death.14 Every parent and adult deserves to know all the facts so they can give fully informed consent.

Who Will do the Screening?: It is proposed that maternal and child nurses in community health services will expand existing physical checks to include mental health screening. They will refer the identified child for “final diagnosis” which will again be based on a subjective checklist ─ no scientific tests. [Productivity Commission Final Report, Vol. 2, p. 204.]

Depending on the state, the existing physical checks are recommended for the infant/child at: 1-4 weeks old, 6-8 weeks, 6 months, 12 months, 18 months, 2 years and 3 years old. So this subjective mental health screening would be done it appears multiple times.15

The Productivity Commission has said there is no adequate data to assess whether the increased focus on infant emotional wellbeing in the past has had a substantial effect on young children and their families. Despite this complete lack of evidence, it is full steam ahead with the screening proposals accompanied with more demands for money in the Final report recommendations. State and Territory Governments will need to commit to funds for this screening. [Productivity Commission Final Report, Vol. 2, p. 205; Productivity Commission Draft Report, Vol. 2, pgs. 653, 658, Vol. 1, p. 11.]

As early as 2010, the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists who had 8 drug companies support their activities in 2017, were promoting that a, “significant number of infants, children and adolescents experience some form of mental illness,” and were recommending all infants were screened to identify early symptoms of mental illness.16

Screening of 3-Year-Olds was Scrapped in 2015: Psychiatry has already attempted this in the past between 2012 and 2015, with the expansion of a physical check called the Healthy Kids Check to include screening for “mental illness” of 3-year-olds. The expanded check was trialled at 8 Medicare Locals and scrapped in 2015 due to immense public criticism from the public and professionals.17 [Productivity Commission Final Report, Vol. 2, p. 204; Productivity Commission Draft Report, Vol. 2, pgs. 657 & 656.]

Symptoms from this Expanded Healthy Kids Check include: fidgety, easily distracted, acts as if driven by a motor and doesn’t listen to rules.

Responses at the time from professionals to this 3-year-old screening included:

- Psychiatrist Allen Frances who was the DSM–IV Task Force Chair, said the screening of 3-year-olds was “reckless” not evidence-based and could lead to an explosion of false diagnoses that would see youngsters overmedicated and labelled with mental illness.17

- The doctor’s magazine, the Medical Observer conducted a survey of GPs in 2012 and found that two-thirds of GPs disagreed with the expanded Healthy Kids Check with a quarter believing it would lead to misdiagnosis with more psychiatric drugs and a further 41% said the scheme was a waste of money.19

- Child psychiatrist Dr Jon Jureidini, said he was “relieved,” that the proposal for the 3-year-old check had disappeared.” 20

In March 2020, after a Draft Report was released, a Freedom of Information Request to the Productivity Commission requesting all the materials obtained or given to them as part of this inquiry related to the Expanded Healthy Kids Check revealed that they did not even have a copy of the actual Expanded Healthy Kids Check.

Despite all this, psychiatry still wants to use the same guidelines as those used in the dumped Expanded Healthy Kids Check to screen 3 & 4-year-olds before they go to preschool. Again it is proposed the existing health checks currently conducted by maternal and child health nurses be expanded to include this mental health screening. There are an estimated 636,618 children aged 3 & 4 who could be put at risk of psychiatric drugs if this proposal goes ahead.21 State and Territory Governments will also have to provide funds for this recommendation. [Productivity Commission Final Report, Vol. 2, pgs. 203, 204, 205; Productivity Commission Draft Report, Vol. 2, p. 658.]

The previous Spending Wasted on Early Intervention: The Productivity Commission clearly stated in one of their reports that despite spending billions of dollars, countless hours of work by teachers, education professionals, doctors, nurses, specialists on early intervention and prevention measures ─ improvements in the mental health of children and young people have been limited. It further stated, “there is very little information to allow us to determine whether investments in mental health and wellbeing are delivering improvements and what policy initiatives have been effective.” [Productivity Commission Draft Report, Vol. 2, pgs. 650, 693.]

The previous Spending Wasted on Early Intervention: The Productivity Commission clearly stated in one of their reports that despite spending billions of dollars, countless hours of work by teachers, education professionals, doctors, nurses, specialists on early intervention and prevention measures ─ improvements in the mental health of children and young people have been limited. It further stated, “there is very little information to allow us to determine whether investments in mental health and wellbeing are delivering improvements and what policy initiatives have been effective.” [Productivity Commission Draft Report, Vol. 2, pgs. 650, 693.]

Early Childhood Education Centres and Schools Being Turned into Mental Health Clinics: The Draft and Final Reports say early childhood education centres and schools act as the gateway for students and families into the mental health system. However, this usurps the role of early childhood education centres and schools: to be places of education, not clinics. Instead, already overworked teachers are being expected to be an adjunct to psychiatry, screening students for mental health problems and to refer them for a diagnosis. [Productivity Commission Final Report, Vol. 1, p. 206; Productivity Commission Draft Report, Vol. 2, pgs. 662, 659.]

We already have a serious problem with Australian children being given antidepressants. There were more than 175,000 children and youth under 19 on antidepressants in 2019, a 26 % increase in just 4 years, despite the fact they are not approved for children under the age of 18 for depression.22 There were 107,000 children on ADHD drugs in 2017.23

Existing Screening Checklists for Children Aged 4 and Above: Include such questions as has trouble sleeping, wants to be with you more than before, is afraid of new situations, fidgets and squirms, distracted, acts as if driven by a motor, does not listen to rules, avoids schoolwork and homework, and refuses to share.24

Increasing Number of Suicides: Since 2008/09 suicides in young people have increased by almost 40%, concurrent with the use of antidepressants increasing approximately 60% in young people.25 Australia’s drug regulatory agency has issued 67 psychiatric drug warnings with 7 of these to warn of the risk of suicidal behaviour with antidepressants26 and as previously stated they are not approved for use in children under 18 for depression.27

Australia’s Drug Regulatory Agency’s database in January 2019 revealed there have been 140 completed suicides, 326 suicide attempts and 606 reports of suicidal ideation linked to antidepressants.28 While not everyone who is on an antidepressant will commit or attempt suicide, clearly some do.

The Productivity Commission advised that “There has been no significant and sustained reduction in the death rate from suicide over the past decade, despite ongoing efforts to make suicide prevention more effective.” [Productivity Commission Inquiry Draft Report, Vol. 1, p. 14.]

While it is excellent that Australia’s drug regulatory agency is currently conducting further inquiries into the link between antidepressants and suicide in children and youth, this needs to be expanded to all psychiatric drugs and all ages.29

Psychiatry’s Abusive Treatments were Not Investigated: There is no evidence in the Draft or Final Reports that the potential harm of electroshock was investigated as a “treatment” for children and adults. In 2019/20 Medicare funded 35,166 electroshock “treatments.”30 Electroshock can cause brain damage, permanent memory loss, cardiovascular complications and death and should be banned.

There is also no evidence in the Reports that the harm caused by restraint including chemical restraint was investigated as a cause for failed treatments and abuse. In 2019/20 there were a staggering 18,352 physical restraint incidents, an increase of 28% in 4 years. Mechanical restraint was used 1,213 times in 2019/20, an increase of 52% in 4 years.31

Psychiatric “treatments” must be investigated as one of the reasons for the increased spending, yet consistently failing mental health system.

Conflicts of Interest: Conflicts of interest between psychiatrists, mental health support groups and pharmaceutical companies is an area which drives up the use of psychiatric drugs. Conflicts were not covered as a reason for the soaring costs with no results and increasing harm in the Draft or Final Report.

Conflicts of Interest: Conflicts of interest between psychiatrists, mental health support groups and pharmaceutical companies is an area which drives up the use of psychiatric drugs. Conflicts were not covered as a reason for the soaring costs with no results and increasing harm in the Draft or Final Report.

No-one responsible for advising governments, involved in writing medical guidelines, conducting inquiries or doing anything that affects entire populations with potential conflicts of interest should take part in these advisory activities. Failure to declare conflicts of interest threatens public trust.

Wasted Tax Payers Money and No Real Help: For years experts have said there is inadequate or no accountability for huge amounts of money spent, which was the reason for this inquiry. Spending has increased by 68% in the past ten years, now reaching nearly $10.6 billion annually.32

Wasted Tax Payers Money and No Real Help: For years experts have said there is inadequate or no accountability for huge amounts of money spent, which was the reason for this inquiry. Spending has increased by 68% in the past ten years, now reaching nearly $10.6 billion annually.32

The Draft Report of the Inquiry stated, “Despite the rising expenditure on healthcare, there has been no clear indication that the mental health of the population has improved.” Yet as the solution, it is irrationally proposed that even more funding is the answer to further expand these failing ineffective programs. [Productivity Commission Inquiry into Mental Health Draft Report, Vol. 1, p. 9.]

The Productivity Commission’s Report on Government Services 2019, reveals that in

2016/17 results were appalling:

- 62.8% of children aged 0-17 discharged from ongoing community care did not

significantly improve. - 40.9% of children aged 0-17 discharged from a psychiatric ward/facility did

not significantly improve. - 44.6% of children aged 0-17 discharged from community care did not

significantly improve. - 14.9% or 14,781 of those who were admitted to psychiatric acute inpatient

services were readmitted to acute wards again within 28 days.33

In the West Australia Auditor-General Report, Access to State-Managed Adult Mental Health Services 2019-20, it states, “126 people spent more than 365 consecutive days in an acute hospital bed. The hospital fees alone for these providers during this period cost the public system an estimated $115 million.”34 This is an average of $2,500 per person per day or $17,500.00 per week per person!

The continual cry for more funding in the Final Report and lack thereof is not the cause of the problem. Factually if psychiatry and its treatments were working there would be a reduction in children and adults requiring assistance. No other sector of society could consistently produce such poor outcomes with tax-payer’s money and expect government handouts to keep increasing, so they can provide even more bad results.

Money given for other areas of medicine show noticeable progress such as improving survival rates for cardiovascular disease over the past 20 years.35

There must be real accountability in the mental health system and real help that returns children and adults to happy and productive lives. When the very science behind something is wrong and the psychiatric system itself is abusive, no amount of money thrown at it will improve the system.

The Real Cost and the Solution: The real cost is not money but destroyed lives, no real help and deaths. Australia’s drug regulatory agency reports as of January 2019, there were 1,707 deaths linked to antidepressants and antipsychotics.36 In February 2021, an article in the Australian Prescriber reported that probably less than 5% of adverse reactions are reported, the number of deaths can only be much higher.37

There is no doubt whatsoever that children and adults get depressed, sad, troubled, anxious or nervous or even act psychotic. The question then is simple ─ is this due to some “mental disease” that can be verified as one would verify cancer or a real medical condition? The answer is no.

Children and adults should be given holistic, humane care that improves their condition. Medical studies have proven that this should include medical tests to determine if the problem is caused by an undiagnosed medical condition.

If a child is exhibiting unwanted behaviour in school, they may be behind and need tutoring or educational basics. The use of phonics and a small dictionary can also assist learning. Some children are very intelligent and gifted and become bored, start to fidget and become a problem as they need a more challenging curriculum. There may also be a lack of interest, the real test is how much attention can a child give to what they like doing?

Medical doctors recommend a good diet, sufficient sleep and exercise.

Facilities should be safe havens where adults and children voluntarily seek help without fear of indefinite incarceration and harmful or terrifying treatment. They need a quiet and safe environment where they can get workable and accountable help for their problems. The existing money spent needs to be re-directed into proven workable solutions.

The solution can’t be more screening or more of the same failing “treatments” and programs.

EXCELLENT RECOMMENDATIONS

There are some excellent recommendations that will protect vulnerable children and adults that must be implemented immediately. These include:

- The Australian Government should require that all mental health prescriptions include a clear and prominent statement saying that clinicians should have discussed possible side effects and proposed evidence-based alternatives to psychiatric drugs prior to prescribing. [Productivity Commission Final Report, Actions and Findings, p. 21.]

- Another excellent recommendation is that children should be kept separate from adults in psychiatric wards. [Productivity Commission Final Report, Actions and Findings, p. 27.]

- In addition, the recommendation that state governments provide free legal assistance to assist with Tribunal Hearings and other hearings for children and adults who are involuntarily detained and being forcibly treated is needed immediately. [Productivity Commission Final Report, Actions and Findings, p. 27.]

The findings of the Final Report are being investigated by a Federal Parliamentary Committee to determine which recommendations will be implemented. More hearings will also be held during 2021. Submissions closed on 24 March 2021. The Committee will release their final report by 1 November 2021.

Sign up to track the Federal Parliamentary Committee and receive emails from Federal Parliament regarding when their initial report in April 2021 is released and when hearings are commencing.

Home page of Select Committee into Mental Health and Suicide Prevention, a Select Committee is a short term committee.

TAKE ACTION

Visit, phone, write or email the below and do the following:

- Advise them of the recommendations and harm they will cause to our infants and toddlers.

- Request that they do not support funding for the harmful recommendations.

- Ask them to take action to ensure existing funding is re-directed to programs proven to help children and that don’t harm, including for the recommendation of programs such as ensuring that every mental health prescription includes a clear and prominent statement saying that clinicians should have discussed possible side effects and proposed evidence-based alternatives to psychiatric drugs prior to prescribing.

- Ask for an inquiry that actually fully investigates all psychiatric treatments including psychiatric drugs as the reason behind Australia’s failing mental health system.

Prime Minister: Hon Scott Morrison, PO Box 6022, Parliament House, Canberra ACT 2600 • Emails can only be sent from his website: www.pm.gov.au/contact-your-pm

Opposition Leader: Hon Anthony Albanese, PO Box 6022, Parliament House, Canberra ACT 2600 • Phone: 02 6277 4022 • Email: A. Albanese.MP@aph.gov.au

Treasurer: Hon Josh Frydenberg, PO Box 6022, Parliament House, Canberra ACT 2600 • Phone: 02 6277 7340 • Email: josh.frydenberg.mp@aph.gov.au

Shadow Treasurer: Dr Jim Chalmers, PO Box 6022, Parliament House, Canberra ACT 2600 • Phone: 02 6277 4880 • Email: jim.chalmers.mp@aph.gov.au

Minister for Health: Hon Greg Hunt, PO Box 6022, Parliament House, Canberra ACT 2600 • Phone: 02 6277 7220 • Email: greg.hunt.mp@aph.gov.au

Shadow Minister for Health: Hon Chris Bowen, PO Box 6022, Parliament House, Canberra ACT 2600 • Phone: 02 6277 4822 • Email: chris.bowen.mp@aph.gov.au

Leader of Opposition in Senate: Senator the Hon Penny Wong, PO Box 6237, Halifax St. Adelaide SA 5000 • Phone: 08 8212 8272 • Email: senator.wong@aph.gov.au

Deputy Leader of Opposition in Senate: Senator the Hon Kristina Keneally, PO Box W4, Parramatta Westfield, NSW 2150 • Phone: 02 9891 9139 • Email: senator.keneally@aph.gov.au

Also contact your local Federal Member of Parliament and local Senator at:

www.aph.gov.au/Senators_and_Members/

State funding will be required for the recommendations for 0-3 year olds and 3 & 4 year olds, so please also contact the equivalent in your state and your local Member of Parliament. Find their contact details below:

NSW: www.parliament.nsw.gov.au/members/pages/all-members.aspx

Vic: www.parliament.vic.gov.au/about/people-in-parliament/members-search/list-all-members

Qld: www.parliament.qld.gov.au/members/current/list

WA: www.parliament.wa.gov.au/parliament/memblist.nsf/WebCurrentMembLA

SA: www.parliament.sa.gov.au/en/Members/Members-Home

Tas: www.parliament.tas.gov.au/ha/halists.pdf

ACT: www.parliament.act.gov.au/members/members-of-the-assembly

NT: parliament.nt.gov.au/members/by-name

You can also contact CCHR on national@cchr.org.au to obtain free copies of the fact sheet.

The Productivity Commission’s Final Report can be accessed on this link: https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/mental-health/report

- “Number of patients dispensed one or more mental health –related prescriptions, by patient demographic characteristics, 2018-19,” Table PBS.4, Mental Health Services in Australia, click on Excel spreadsheet under the blue bar graph. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/mental-health-services/mental-health-services-in-australia/report-contents/mental-health-related-prescriptions/prescriptions

- Contract Notice ID numbers: CN99216, CN824891, CN415063, CN348304, CN205813, CN445908, CN41201, Aus Tender, Australian Government. https://www.tenders.gov.au/Search/KeywordSearch?keyword=Harvey+Whiteford

- Productivity Commission Mental Health Inquiry Final Report, Volume 1, No. 95, 30 June 2020, released on 16 November 2020, pages 101, 121 & p. 763 for “APA 2013” reference. https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/mental-health/report#fs2 ; Australian Government Productivity Commission, Mental Health Productivity Commission Inquiry Draft Report, Vol 1, p.124, 147, 149, 150 & p. 1164, Vol 2, “APA 2013” reference, October 2019. https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/mental-health/draft/mental-health-draft-volume1.pdf and https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/mental-health/draft/mental-health-draft-volume2.pdf

- Australian Association for Infant Mental Health (AAIMH), Infant Mental Health Training Information, accessed 16 Feb 2021, https://www.aaimh.org.au/branches/wa/imh-training-info/

- Examples of no tests include: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision, DSM-IV-TR, American Psychiatric Association, pages 88 , 89, 305; Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, DSM-5, American Psychiatric Association, pages.61, 101.

- Examples of DSM usage: Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme, atomoxetine entry (Strattera), click on “Authority Required (Streamlined),” http://www.pbs.gov.au/medicine/item/9094P; Australian Government, Department of Health, 5 Apr.2021. Medicare Benefits Schedule entry for psychiatric attendance (item 319), AN.0.31, MBS Online, Australian Government, Department of Health, 5 Apr.2021. Click on “Associated Notes,” http://www9.health.gov.au/mbs/fullDisplay.cfm?type=note&q=AN.0.31&qt=noteID&criteria=DSM%20IV and http://www9.health.gov.au/mbs/fullDisplay.cfm?type=item&q=90250&qt=item&criteria=90250

- Simone Darling, Frank Oberklaid, “Child mental health: building a shared language,” Insight, 16 Sept 2019. https://insightplus.mja.com.au/2019/36/child-mental-health-building-a-shared-language/

- Australian Government Productivity Commission, Mental Health Productivity Commission Inquiry Draft Report, Vol. 2, pages 652, 650, 656 and Vol. 1, p.186, October 2019, https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/mental-health/draft/mental-health-draft-volume1.pdf and https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/mental-health/draft/mental-health-draft-volume2.pdf

- The DC:0-3 Casebook, Zero to Three, National Center for Infants Toddlers and Families, 1997, p.21, 22.; C.H. Zeanah, A.S. Carter, J. Cohen, M.M. Gleason, M. Keren, A. Lieberman, K.M.C Oser, “Introducing a New Classification of Early Childhood Disorders: DC:0-5,” ZERO TO THREE, January 2017; The DC:0-5 Diagnostic Classification of Mental Health and Developmental Disorders of Infancy and Early Childhood, Zero to Three, 2016, pages, 26, 30, 51, 52,92, 99.

- Imogen Neale, “Ministry hides test’s real purpose,” Stuff, 25 June 2012. http://www.stuff.co.nz/dominion-post/news/politics/7160837/Ministry-hides-tests-real-purpose

- “Table 1. Number of patients who had at least one prescription filled for PBS/RPBS listed antidepressant drug in 2007/08 year by age and State/Territory. Department of Health and Ageing, 2008, https://cchr.org.au/ptanegul/2016/08/Antidepressants-2007-2008.pdf ; “Table 1. Number of patients who had at least one prescription filled for PBS/RPBS listed antipsychotic drug in 2007/08 year by age and State/Territory. Department of Health and Ageing, 2008, https://cchr.org.au/ptanegul/2016/08/Antipsychotics-2007-2008.pdf ; “Number of Patients on Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) Drugs,” Freedom of Information Request No: 112/0708, Department of Health and Ageing, 2008 https://cchr.org.au/ptanegul/2017/02/Part-1-of-numbers-on-ADHD-drugs-2007.pdf

- “Report 3A, Number of Unique Patients by Patient Age Group and Patient State for Requested ADHD Items Supplied from 1 January 2015 to 31 December 2015,” Request Number- MI5329, Department of Human Services, Strategic Information Division, Information Services Branch, 27 May 2016. https://cchr.org.au/ptanegul/2016/08/Numbers-on-ADHD-Drugs-30-May-2016.pdf ; “Report 1A, Number of Unique Patients by Patient Age Group and Patient State for Requested Antidepressant Items Supplied from 1 January 2015 to 31 December 2015,” Request Number-MI5329, Department of Human Services, Strategic Information Division, Information Services Branch, 27 May 2016. https://cchr.org.au/ptanegul/2016/08/Numbers-on-Antidepressants-30-May-2016.pdf ; Report 2A, Number of Unique Patients by Patient Age Group and Patient State for Requested Antipsychotics Items Supplied from 1 January 2015 to 31 December 2015,” Request Number- MI5329, Department of Human Services, Strategic Information Division, Information Services Branch, 27 May 2016. https://cchr.org.au/ptanegul/2016/08/Numbers-on-Antipsychotics-30-May-2016.pdf;

- “Table PBS.4: Number of patients dispensed one or more mental health –related prescriptions, by patient demographic characteristics, 2018-19,” Mental Health Services in Australia, click on Excel spreadsheet under the blue bar graph. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/mental-health-services/mental-health-services-in-australia/report-contents/mental-health-related-prescriptions/prescriptions

- “Evidence Summary: Identification of young people at risk of developing psychosis,” headspace National Youth Mental Health Foundation, 2015. p.4. https://headspace.org.au/assets/Uploads/Evidence-Summary-Identification-of-Young-People-at-Risk-Developing-Psychosis.pdf

- Fully referenced layman’s summary of all psychiatric drug warnings issued by Therapeutic Goods Administration, https://cchr.org.au/ptanegul/2018/10/Australian-government-warnings-on-psychotropic-drugs-180801.pdf

- “My personal health record,” NSW Ministry of Health, 2019, p. 3. https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/kidsfamilies/MCFhealth/Publications/blue-book.pdf

- 2019 Financial Report, The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists, 24 March 2020, p. 9. https://www.ranzcp.org/files/about_us/annual-reports-and-strategy/ranzcp-2019-financial-report.aspx; Prevention and early intervention of mental illness in infants, children and adolescents: Planning strategies for Australia and New Zealand, 2010. The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists: Report from the Faculty of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, p. 20

- Karyn E Alexander and Danielle Mazza, “Scrapping the Healthy Kids Check: a lost opportunity, MJA, Volume 203, Issue 8, 19 Oct. 2015. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2015/203/8/scrapping-healthy-kids-check-lost-opportunity

- Sue Dunlevy, “Child health check ‘is reckless,’” The Australian, 12 June 2012, p.2.

- Neil Bramwell, “Two-thirds of GP’s disagree with well-being check,” Medical Observer, 18 Sept. 2012.

- Sarah Colyer, “Axing kids check retrograde,” MJA Insight, 19 October 2015.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, 31010DO002_201906 Australian Demographic Statistics, June 2019, Table 7 Estimated resident population, by age and sex –at 30 June 2018. https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/3101.0Jun%202019?OpenDocument

- “Antidepressant utilisation and risk of suicide in young people, Safety investigation Version 1.0,” Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration, p. 48, December 2020. https://www.tga.gov.au/sites/default/files/antidepressant-utilisation-and-risk-suicide-young-people.docx

- Dr Bernie Towler Commonwealth’s Principal Medical Adviser, testimony to United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child, 12.30 minutes on UN video of testimony, 10 Sept. 2019. http://webtv.un.org/search/consideration-of-australia-contd-2403rd-meeCng-82nd-session-commiXee-on-the-rights-of-the-child/6084998390001/?term=&lan=english&page=8

- “Paediatric Symptom Checklist,” Beyond Blue, on their website page titled, “Child Mental Health Checklist,” for kids aged 4 to 16, https://healthyfamilies.beyondblue.org.au/age-6-12/mental-health-conditions-in-children/child-mental-health-checklist ; “Connors 3rd EdiCon-Connors 3-Teacher Assessment Report,” C Keith Connors, using DSM-5, 2014, p. 5. https://paa.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Conners-3-Teacher-Assessment-Report.pdf

- Sue Dunlevy, “Happy drugs in link with Suicide,” Courier Mail, 2 June 2019, p. 5; Dr Martin Whitely, Dr Melissa Raven, “More young Australians suicide/self-harm and use antidepressants while experts dismiss FDA warning,” PsychWatch Australia, 1 June 2019, https://www.psychwatchaustralia.com/post/more-young-australians-suicide-self-harm-and-use-antidepressants-while-experts-dismiss-fda-warning

- Department of Health and Ageing Therapeutic Goods Administration, Medicines Safety Update, “Medicines associated with a risk of neuropsychiatric adverse events,” Volume 9, Number 2, June 2018; Department of Health and Ageing Therapeutic Goods Administration, Medicines Safety Update, “Antidepressants – Communicating risks and benefits to patients,” Volume 7, Number 5, October-December 2016; Department of Health and Ageing Therapeutic Goods Administration, Medicines Safety Update, “Atomoxetine and suicidality in children and adolescents,” Volume 4, Number 5, October 2013; “Australian ADHD drug warnings are already in place: TGA,” AAP Newswire 22 February, 2007; “Suicidality with SSRIs: adults and children,” The Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration, Adverse Drug Reactions Bulletin, Vol. 24, No. 4, August 2005; “Use of SSRI antidepressants in children and adolescents” The Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration, Adverse Drug Reactions Bulletin, Vol. 23, No. 6, August 2004; “Warnings for high dose tricyclics antidepressants,” The Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration, Adverse Drug Reactions Bulletin, Vol. 23, No. 5, October 2004.

- “Suicidality with SSRIs: adults and children,” The Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration, Adverse Drug Reactions Bulletin, Vol. 24, No. 4, August 2005.

- Therapeutic Goods Administration Database of Adverse Event Notifications-Medicines, List of reports generated for each antidepressant & antipsychotic, as of December 2019 and added manually. https://www.tga.gov.au/database-adverse-event-notifications-daen

- “Antidepressant utilisation and risk of suicide in young people,” Therapeutic Goods Administration, 9 December 2020. https://www.tga/gov.au/alert/antidepressant-utilisation-and-risk-of-suicide-young-people

- Statistics generated on Medicare Australia website using MBS item codes: 14224 for electroconvulsive therapy. https://www.medicareaustralia.gov.au/statistics/mbs_item.shtml

- “Mental health services in Australia, Restraint”, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 29 January 2021. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/mental-health-services/mental-health-services-in-australia/report-contents/restrictive-practices/restraint; “Table RP.5:Restraint rate, public acute sector acute health hospital services, states and territories, 2015-16 to 2018-18, Mental Health Services Restrictive Practices, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Note: Queensland did not report the use of physical restraint except for 2017/18 and WA did not report mechanical restraint for any of these years. Download Excel spreadsheet on this link, see under blue bar graph on webpage to download, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/mental-health-services/mental-health-services-in-australia/report-contents/restrictive-practices/restraint

- “2012 Mental Health Services in Brief,” Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2012, p. 23; “2013 Mental Health Services in Brief,” Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2013, p. 28; “2014 Mental Health Services in Brief,” Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2014, p. 18; “2015 Mental Health Services in Brief,” Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2015, p. 18; “2016 Mental Health Services in Brief,” Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2016, p .24; “2017 Mental Health Services in Brief,” Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2017, p. 25; “2018 Mental Health Services in Brief,” Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2018, p. 29; 2019 Mental Health Services in Brief,” Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2019, p. 30; Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2020. Mental health services in Australia. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 23 September 2020, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/mental-health-services/mental-health-services-in-australia ; “Mental Health services in Australia: Expenditure on mental health services, Table EXP.34: Expenditure ($ million) on mental health services, by source of funding, 1192-93 to 2018-19, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 29 Jan 2021. Download spreadsheet under blue bar graph. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/mental-health-services/mental-health-services-in-australia/report-contents/expenditure-on-mental-health-related-services

- “Productivity Commission Report on Government Services 2020,” Part E, ‘rogs-2020-parte-sector-overview-data-tables.xls’, Table 13A.62, Table13A.34, https://www.pc.gov.au/research/ongoing/report-on-government-services/2020/health/rogs-2020-parte-sector-overview-data-tables.xlsx or for the report overview itself https://www.pc.gov.au/reserch/ongoing/report-on-government-services/2020/health ; “Mental Health Management, Table 13A.34, Table 13A.62, Part E, Chapter 13, Mental Health Management,” Report on Government Services 2019, Australian Government, Productivity Commission, 30 January. 2019. https://www.pc.gov.au/research/ongoing/report-on-government-services/2019/health/mental-health-management/rogs-2019-parte-chapter13.pdf

- Western Australian Auditor General’s Report “Access to State-Managed Adult mental health Services”, Report 4: 2019-20, 14 August 2019, page 25, https://audit.wa.gov.au/reports-and-publications/reports/access-to-state-managed-adult-mental-health-services/

- Cardiovascular disease: most deaths and highest costs, but situation improving, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, https://www.aihw.gov.au/news-media/media-releases/2011/2011-mar/cardiovascular-disease-most-deaths-and-highest-co

- Therapeutic Goods Administration Database of Adverse Event Notifications-Medicines, List of reports generated for each antidepressant, as of 05/03/2020 and added manually. https://www.tga.gov.au/database-adverse-event-notifications-daen ; Therapeutic Goods Administration Database of Adverse Event Notifications-Medicines, List of reports generated for each antipsychotic, as of 05/03/2020 and added manually. https://www.tga.gov.au/database-adverse-event-notifications-daen

- Martin JH, Lucas C, Editorial: “Reporting adverse drug events to the Therapeutic Goods Administration”, Australian Prescriber, Issue 1, February, https://www.nps.org.au/australian-prescriber/articles/reporting-adverse-drug-events-to-the-therapeutic-goods-administration